Remarkable projects, shaped by daylight

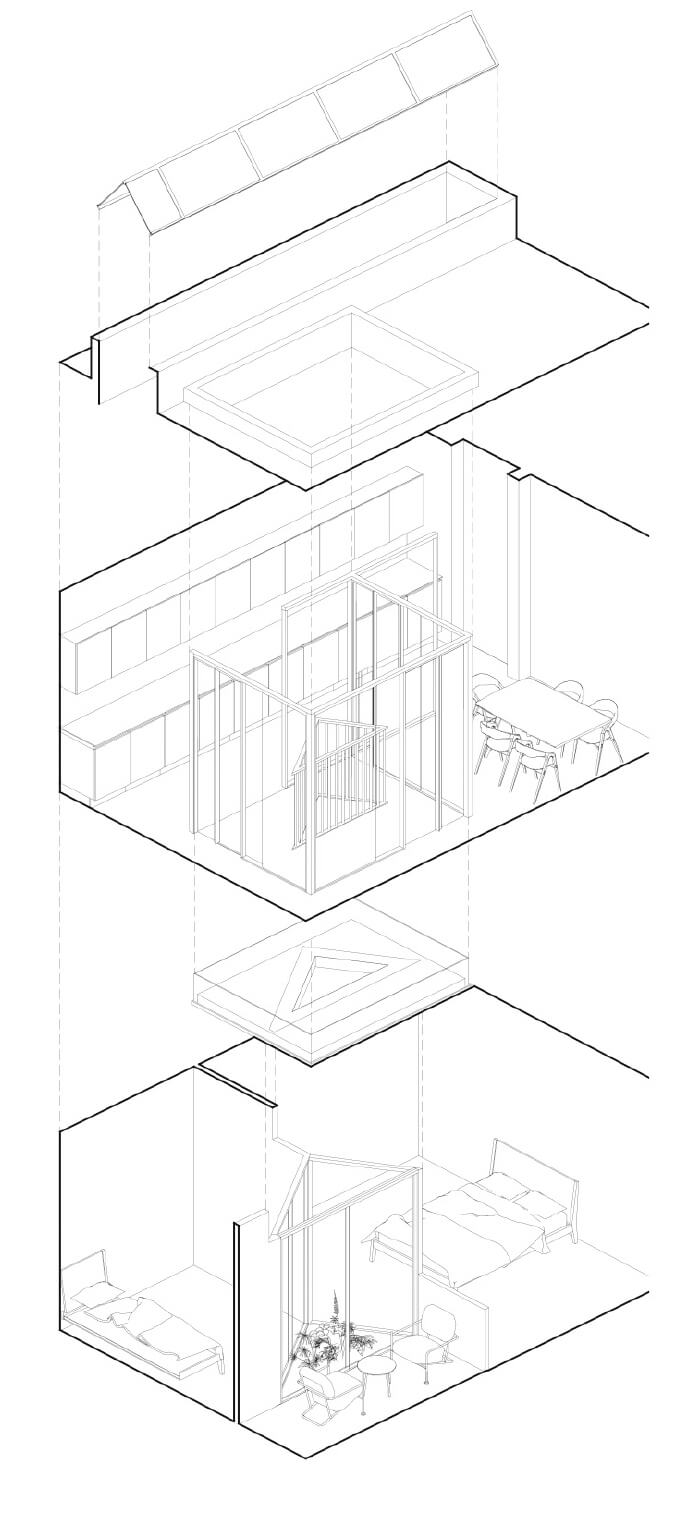

The competition tasked entrants to design a generous family home for a compact site that was enclosed on all sides, so that the only access to daylight is from the sky directly above.

Winner | Stephen Macbean, Blink House

Macbean’s design had a ‘confidence about technology’, noted the judges

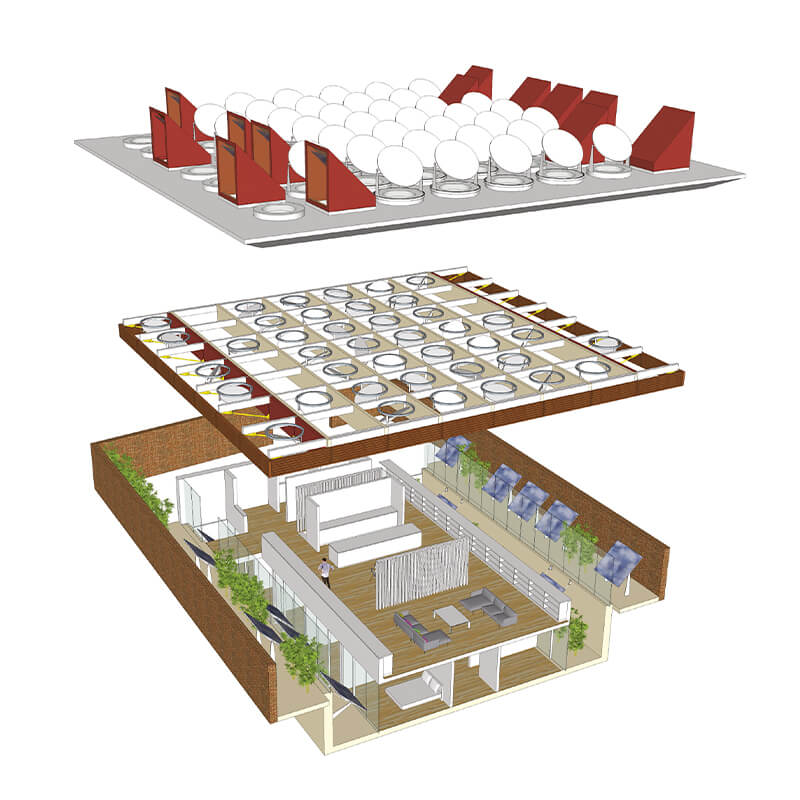

Obscured on all sides by a high brick wall, a busy road, a narrow lane and a park, Stephen Macbean’s winning entry, Blink House, uses ingenious rooflights to direct its occupants’ vision skyward.

Macbean’s proposal involves excavating the basement, providing two linear, top-lit gardens at the east and west and creating a grid structure on the roof at 2.4m centres. This grid forms part of Blink House’s ‘fantastical’ lighting solution: a combination of skylights, reflective baffles and ‘windowscopes’ – sculptural periscopes acting in lieu of windows to provide horizontal views.

At the lower levels, the periscopic effect is created by large, angled mirrors placed within the linear gardens, offering curated views outwards. On the roof, to the edges of the system of skylights, are mirrors housed in Corten steel-clad insulated cowls.

Learn more

Above and below the roof openings containing the circular skylights are the mechanised white aluminium baffle discs, which are able to rotate and tilt. These offer residents a degree of control over how light enters and acts within the interior spaces. Within the rim of each internal baffle, circular LED strips provide additional direct or indirect lighting options and create a ‘visually rhythmic’ ceiling plane.

Macbean’s design had a ‘confidence about technology’, noted the judges. Unusually, Macbean also presented photos of a physical model to prove the idea’s efficacy. He also gave thought to the street elevation – the roof appears to float above the perimeter wall, mediated by louvres which provide further lighting control and ventilation.

The judges praised its ‘wow factor’, its flexibility, its privacy and its willingness to embrace and control the constantly changing sky views and attendant interior light conditions. As Chris Foges summarised: ‘Blink House is in the spirit of the competition, which is to say: don’t dismiss difficult sites as impossible, as ingenuity and imagination can find a way.’ ‘I like its weirdness,’ remarked Gianni Botsford.

Commended

Martin Gruenanger, Invisible House

The range of materials and unique solutions impressed the judges

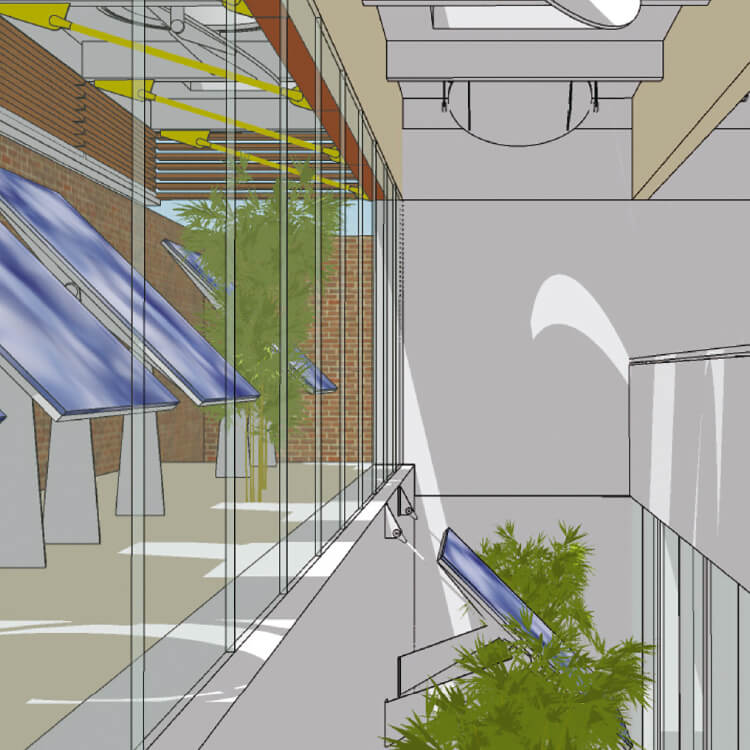

Martin Gruenanger’s Invisible House is an extension to a previous project by Space Group Architects. It doubles the floor area and adds a bedroom, living room, storage space and gym.

Daylight and natural ventilation are provided through a sunken courtyard, carefully positioned walk-on skylights (the roof of the extension is at ground level, abutting the main house) and an abstract ventilation shaft. The interior is finished in fair-faced concrete, lightened by polished stainless-steel fixtures and fittings, which reflect and deflect the natural light.

Added to this is a series of reflective sculptural elements, including an amorphous, mirrored ceiling feature, a ‘metal waterfall’ beneath a skylight and other integrated sculptures.

To soften the stark concrete and metal, oak is used in the staircase while rock outcrops and mosses from the site are incorporated into the interior. A bridge over the courtyard made from structural aluminium and translucent foam filters light in intricate ways. Mirrored panels in a small gym create a seemingly infinite space, akin to a computer game.

The range of materials and unique solutions impressed the judges. ‘The nice thing about this is that there are a lot of different and unusual methods making a play of light, not just lighting the rooms,’ said Tatiana von Preussen. The context of an existing project appealed to Debbie Phillips, who observed that ‘It feels real, and could be applied as a solution to many sites’.

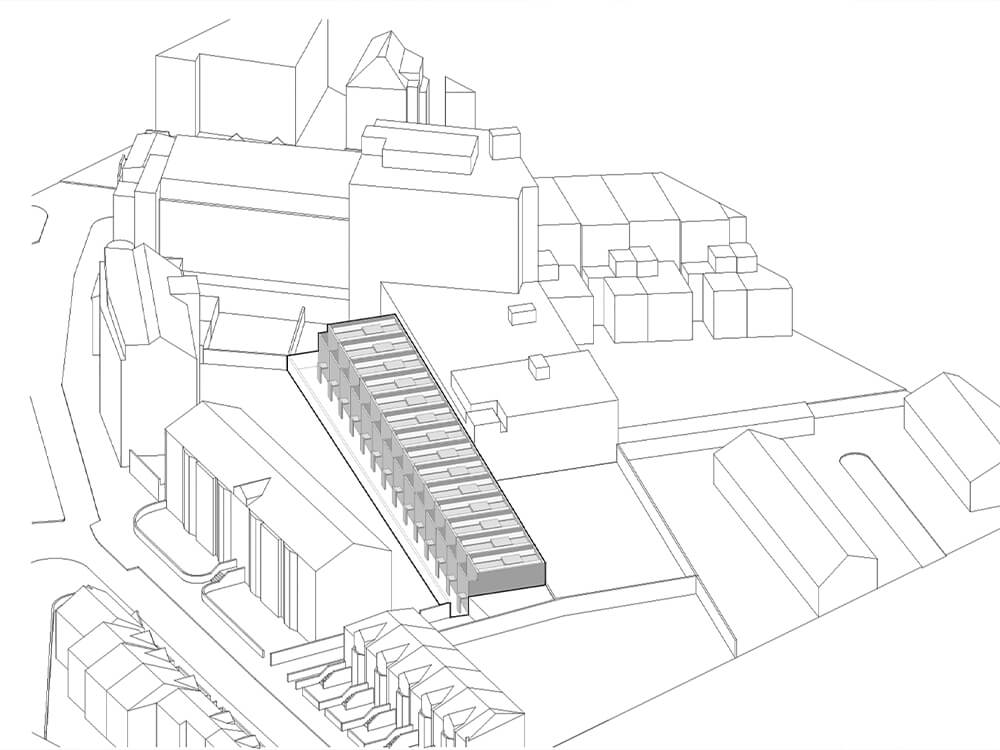

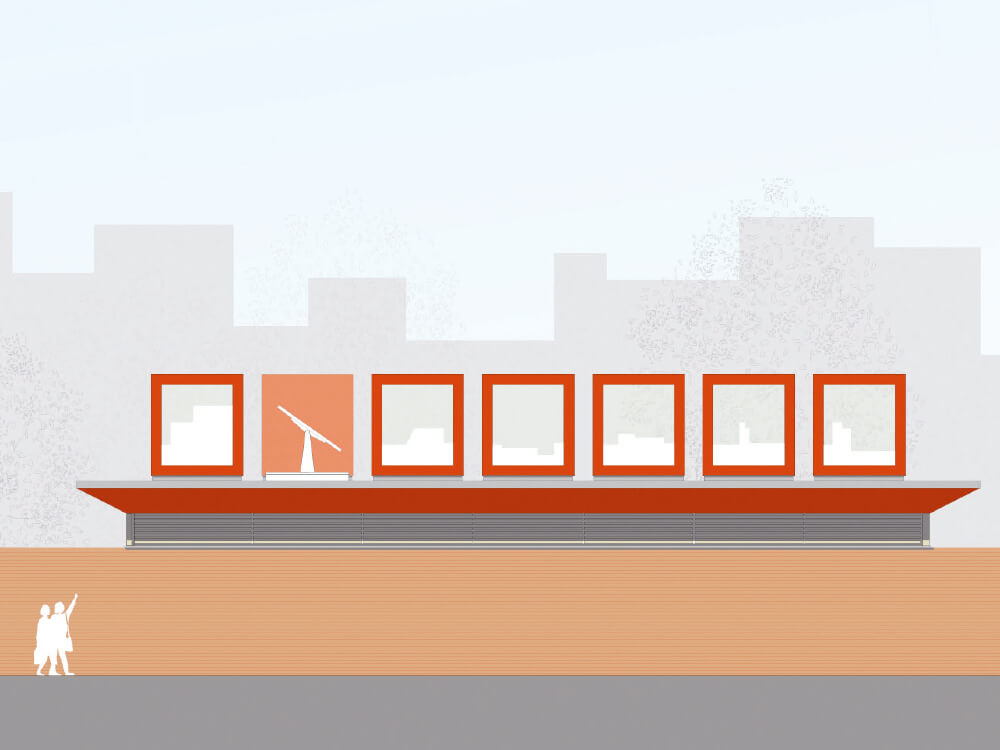

Matthew Bate + Julian Hurley, Back to Back House

The central lightwell can be both inhabited or empty

‘The competition brief points to the scarcity of straightforward sites in densifying cities,’ noted Matthew Bate’s project statement. ‘We suggest that history has met this challenge before in the form of the terrace house and, following this, the back-to-back house of the industrial revolution.’

His proposition takes a landlocked and overlooked site ‘which does not lend itself to traditional building typologies’ and turns it into an opportunity to generate affordable housing provision.

Bate updates the problematic 1800s back-to-back format. He addresses issues of poor lighting and ventilation through the use of a long, triangular roof lantern and another large rooflight, positioned above interconnecting multi-level spaces inspired by the Loosian ‘raumplan’, which challenged the hierarchy of rooms in stacked floors.

Bate’s design sinks a glazed cube into the floorplate, positioning a triangular lightwell at ground-floor level askance to the cuboid above it. The central lightwell can be both inhabited or empty. The device permits views at unexpected angles, encourages fluid movement around it and produces a pleasing cascading, pooling effect with light. ‘It is surprising how the triangular lightwell brings light into the room,’ observed Tatiana von Preussen.

The ‘simple and calm’ interior is a counterpoint to the austere facade, devoid of details. The judges also praised the ‘well-worked-out plan’, its provision of privacy within a dense plot, and its attempt to offer a response to volume housing in constrained conditions.

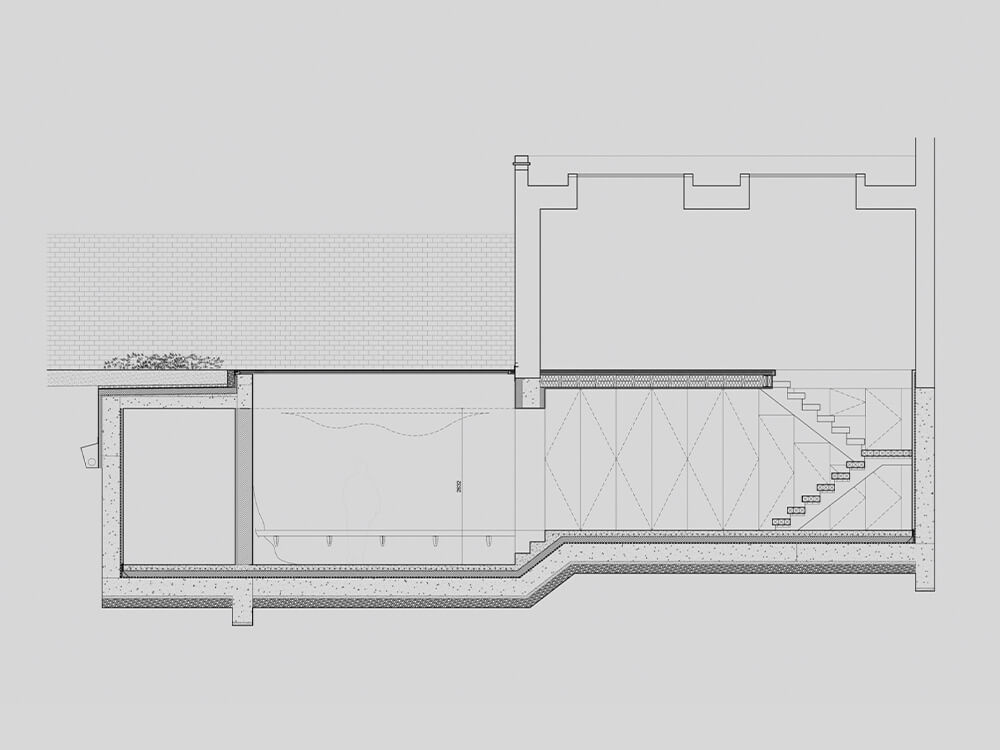

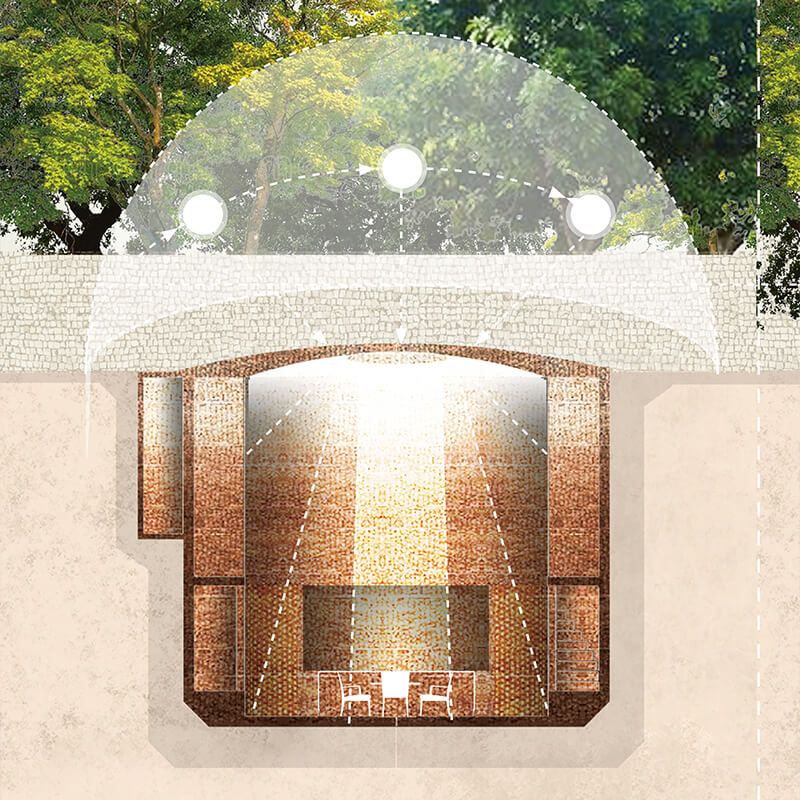

Soraya Somarathne, The Cloister

‘There is no outlook but it does not feel claustrophobic’

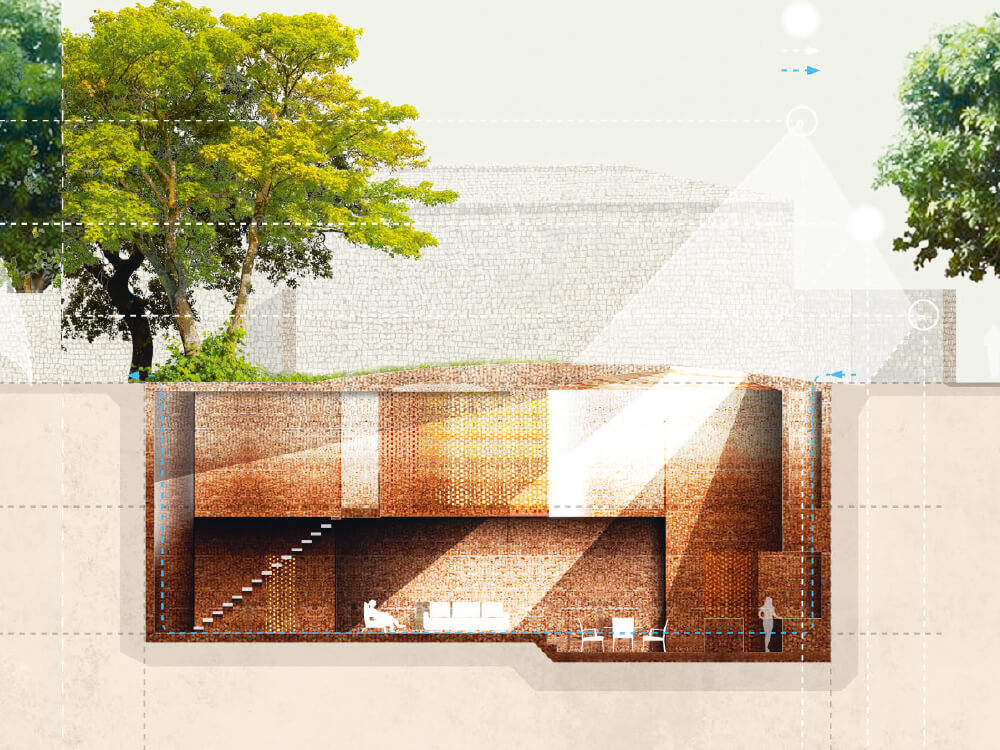

Influenced by its location in the grounds of Lambeth Palace, Soraya Somarathne’s top-lit Cloister offers a meditative and contemplative space for its occupants. The secluded, subterranean residence was admired by the judges for its ‘different sensibility’ and ‘celestial atmosphere’.

Brick is the primary material, tying in with the historic surrounding architecture. Somarathne also incorporates building techniques derived from the ‘Rohtak dome’, a self-supporting shallow brick dome found in the Indian villages of Rohtak, topped by a central skylight. ‘The mounded roof gives the design a certain presence,’ said Foges. ‘In some ways it recalls the Pantheon with its central oculus – there is no outlook but it does not feel claustrophobic’.

The Cloister’s domed ceiling and curved internal walls disperse light throughout the space. Light-tubes within the perforated brickwork around the skylight supplement natural daylighting, taking advantage of the position of the sun throughout the day; the master bedroom enjoys morning sunlight, the kitchen receives midday sun, and the children’s bedroom is warmed by evening light.

During the summer, light is centralised within the house, allowing more of the interior to benefit from cooling shade. Oblique winter sunlight has the opposite effect. ‘Unlike some entries, this one carefully considers the movement of the sun, the seasons, and the changing elements of light,’ said Botsford. ‘These considerations are fundamental, and create different opportunities’.

Sustainability considerations include the use of flexible, cost-effective and eco-friendly clay brick, capable of being recycled at the end of its life. The holes within the structural bricks have been adapted to function as planters, the soil and grass providing additional insulation.